More men to school?

More men to school?

”It’s incredibly hard to capture what gender means for teachership”. So considered a group of a few students in Restaurant Uno in Ruusupuisto. The students were pondering, on the basis of their first weeks at the University, about the female domination among class teachers and its implications for teaching work. What is this phenomenon all about? Why is the teaching profession sought and eventually occupied predominantly by women? Why are there so few men in schools?

”It’s incredibly hard to capture what gender means for teachership”. So considered a group of a few students in Restaurant Uno in Ruusupuisto. The students were pondering, on the basis of their first weeks at the University, about the female domination among class teachers and its implications for teaching work. What is this phenomenon all about? Why is the teaching profession sought and eventually occupied predominantly by women? Why are there so few men in schools?

Career choices start taking shape at elementary school already

According to the recent OECD report Education at Glance (2016), education and teaching fields attract internationally clearly more women than men. Across the 30 countries studied, the share of females among new students in these fields was 67% at minimum. For Finland, this percentage was 83%, which is slightly above the OECD average (78%). The highest percentages of females were found in Italy and Estonia (92% and 90%). Thus, the phenomenon is not limited to Finland or teacher education at the University of Jyväskylä. The gender distribution at our University is well in line with the national trend for the fields of education and teaching, since the share of females among the students starting class teacher studies in 2016 was 86%. According to a report by the National Board of Education (2013), about 75%of those working as class teachers are female.

When we examine the attractiveness of class teacher education from the applicants’ perspective, attention is easily paid to the critical transition phase from upper secondary school to university: Is there at that point sufficient information available and easily accessible about the educational field? Professional orientation begins often much earlier, however, at elementary school already. This notion has been presented by Professor Jacquelynne Eccles (University of California, USA), who was recently promoted an honorary Doctor of the Faculty of Social Sciences. She has investigated, for example, factors influencing educational choices and related gender differences.

According to Eccles, the choice of the educational field is based on the child’s and youth’s gradually evolving understanding about their own qualities and what they might become”. The self-concept as a learner, which evolves during elementary school, plays here an important role. It refers to views on one’s competencies and abilities, and over the school years such views tend to turn into relatively permanent conceptions about one’s personal strengths and weaknesses. The views are based on experiences of success and failure in learning situations. Other influential factors include comparison to classmates as well as feedback and encouragement from parents and teachers (or the lack thereof). For girls, the perceived strengths are often related to mother tongue, whereas boys’ views begin already early to emphasise mathematical and technical skills. For many boys this is directing educational choices to technological fields.

Another important explanatory factor for educational choices, according to Eccles, has to do with the kind of professions and occupations appreciated by men and women. It has been found out in the United States that women, more often than men, seem to appreciate professions that include social interaction and in which they feel they are doing something societally important. Men favour professions and occupations that include working with matters and technical devices enabling strong agency and progress in career. While there are certainly various cultural characteristics involved in occupational appreciations, Eccles’s research findings can help understand female domination in the Finnish teacher education and teacher’s work as well: the core features of the work seem to be linked more closely with the occupational appreciations of women than those of men. Moreover, female candidates outperform males in the national student admission test for the field of education (VAKAVA), which further increases the gender gap among the new students.

Both men and women are needed as teachers

Another issue is that the meaning of the teacher’s gender is hard to specify – as the students in Restaurant Uno were pondering. The scarcity of male teachers in basic education is considered a problem at times, even though research has shown no connection to learning outcomes or to learning motivation. When the students are asked, the gender of teachers seems to have little significance. It is more essential that the teacher has good teaching skills and is friendly and fair, and has a sense of humour. Nevertheless, there is reason to pay attention to the gender distribution of the teaching profession in the future as well. The new framework curriculum for basic education (2014) state that the school community should support students in the development of their gender identity and guide them to recognise and respect human diversity. This goal can be best achieved in a school community where diversity is actualised in many ways, also with regard to teachers’ gender.

It is also important to discuss about the significance of gender in teacher’s work and in teacher education. The perspective needs to be broadened to the questions how gender is related to the ways of learning, what kind of feelings school raises in students of different types, and what kind of agency it enables. It is also worth considering whether the current school sufficiently supports understanding of the diversity related to gender. Does an individual’s– whether student or teacher – experience of his/her own gender receive enough space in educational discussions and in the daily school life?

Riitta-Leena Metsäpelto

Riitta-Leena Metsäpelto (Doctor in Psychology, Adjunct professor) works as a senior researcher in the Centre for Research on Learning and Teaching (CLT).

Read more:

Education at a Glance 2016

Jacquelynne Eccles

Opetushallituksen raportti Opettajat Suomessa 2013 [Teachers in Finland 2013]

Perusopetuksen opetussuunnitelman perusteet 2014 [Framework Curriculum of Basic Education 2014]

Send feedback to the author: riitta-leena.metsapelto@jyu.fi

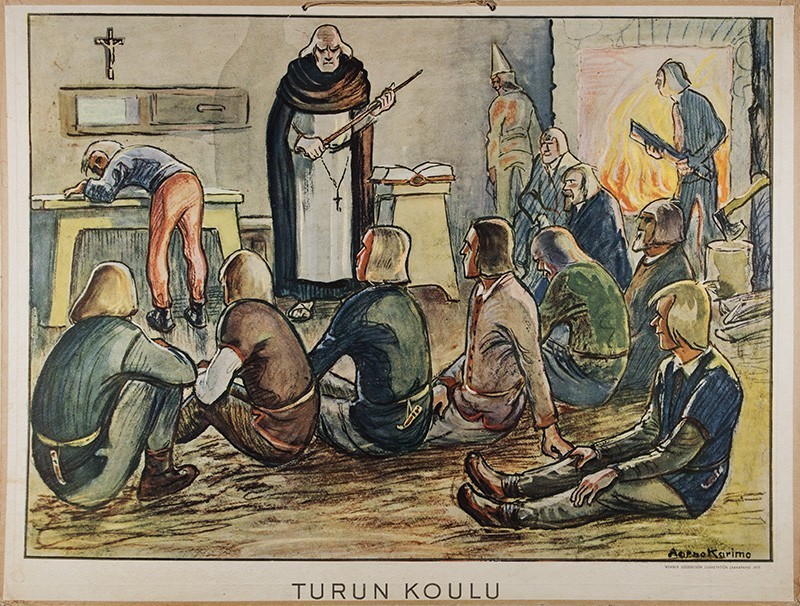

Main image: A teaching chart, a school in Turku (Aarno Karimo) 1935 (Turku Museum Centre); Author's image: Martti Minkkinen.

Translation: Tuomo Suontausta