Class 9

Fonetiikka-harjoitteita

9.luokan englanti 3vvt

|

Oppimismateriaaleina mm. e-materiaali, TOP9-työkirja, lukukirjat ja jakso-opetusaiheita käsittelevä englanninkielinen materiaali. Rakenteiden ja sanaston monipuolinen kertaus. Uusina kielioppiasioina epäsuora esitys, passiivi, infinitiivi ja -ing-muoto. Oppilaat tekevät kirjallisia ja suullisia esitelmiä nuorten kirjallisuuden klassikoista. Tavoitteina aktiivinen kielitaito ja oman ajattelun kehittymisen näkyminen englannin kielen opinnoissa. |

Teksti

Vuosiluokka 9

Tavoitteet

T1 edistää oppilaan taitoa pohtia englannin asemaan ja variantteihin liittyviä ilmiöitä ja arvoja antaa oppilaalle valmiuksia kehittää kulttuurienvälistä toimintakykyä

T2 kannustaa löytämään kiinnostavia englanninkielisiä sisältöjä ja toimintaympäristöjä, jotka laajentavat käsitystä globalisoituvasta maailmasta ja siinä toimimisen mahdollisuuksista

T3 ohjata oppilasta havaitsemaan, millaisia säännönmukaisuuksia englannin kielessä on, miten samoja asioita ilmaistaan muissa kielissä sekä käyttämään kielitiedon käsitteitä oppimisensa tukena

T4 rohkaista oppilasta asettamaan tavoitteita, hyödyntämään monipuolisia tapoja oppia englantia ja arvioimaan oppimistaan itsenäisesti ja yhteistyössä sekä ohjata oppilasta myönteiseen vuorovaikutukseen, jossa tärkeintä on viestin välittyminen

T5 kehittää oppilaan itsenäisyyttä soveltaa luovasti kielitaitoaan sekä jatkuvan kieltenopiskelun valmiuksia

T6 rohkaista oppilasta osallistumaan keskusteluihin monenlaisista oppilaiden ikätasolle ja elämänkokemukseen sopivista aiheista, joissa käsitellään myös mielipiteitä

T7 tukea oppilaan aloitteellisuutta viestinnässä, kompensaatiokeinojen käytössä ja merkitysneuvottelun käymisessä

T8 auttaa oppilasta tunnistamaan viestinnän kulttuurisia piirteitä ja tukea oppilaiden rakentavaa kulttuurienvälistä viestintää

T9 tarjota oppilaalle mahdollisuuksia kuulla ja lukea monenlaisia itselleen merkityksellisiä yleiskielisiä ja yleistajuisia tekstejä erilaisista lähteistä sekä tulkita niitä käyttäen erilaisia strategioita

T10 ohjata oppilasta tuottamaan sekä puhuttua että kirjoitettua tekstiä erilaisiin tarkoituksiin yleisistä ja itselleen merkityksellisistä aiheista kiinnittäen huomiota rakenteiden monipuolisuuteen ja ohjaten hyvään ääntämiseen

Euroopan kielten päivän tehtävät +kielitriviaa

https://edl.ecml.at/Home/tabid/1455/language/fi-FI/Default.aspx

Did you know this about... English?

01 The spelling of William Shakespeare's name has varied over time. Sources from William Shakespeare’s lifetime spell his last name in more than 80 different ways, ranging from “Shappere” to “Shaxberd”. In the handful of signatures that have survived, the Bard never spelled his own name “William Shakespeare,” using variations or abbreviations such as “Willm Shakp,” “Willm Shakspere” and “William Shakspeare” instead. However it’s spelled, Shakespeare is thought to derive from the Old English words “schakken” (“to brandish”) and “speer” (“spear”), and probably referred to a confrontational or argumentative person.

02 In the English language the combination "ough" may be pronounced in nine different ways. The following sentence contains them all: "A rough-coated, dough-faced, thoughtful ploughman strode through the streets of Scarborough; after falling into a slough, he coughed and hiccoughed."

03 There is a completely unique English dialect spoken only on Tangier Island, Virginia. It is said to be almost the same as when the island was settled in 1686 and can be unintelligible even to native English speakers.

04 According to the US company Global Language Monitor (GLM) a new word in the English language is created about every 98 minutes.

The English language is likely to contain the most words of all languages, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, and estimates for the number of words range from one to two million.

05 Before the year 1000, the word “she” didn’t exist in the English language. The singular female reference was the word "heo," which also was the plural of all genders. The word "she" didn't appear until the 12th century, about 400 years after English began to take form. "She" probably derived from the Old English feminine "seo," the Viking word for feminine reference.

06 The word “impossible” dropped in literary use by 50% over the course of the 20th century

07 “The sixth sick sheik’s sixth sheep’s sick” is listed by the Guinness Book of Records as the hardest tongue twister in the world.

08 The word “like” can be used as a noun, verb, adverb, adjective, preposition, particle, conjunction, hedge, interjection, and quotative.

09 Aoccdrnig to a rscheearch at Cmabrigde Uinervtisy, it deosn’t mttaer in waht oredr the ltters in a wrod are; the olny iprmoatnt fatcor is taht the frist and lsat ltteres be at the rghit pclae. The rset can be a total mses and you can sitll raed it wouthit a porbelm. Tihs is bcuseae the huamn mnid deos not raed ervey lteter by istlef, but the wrod as a wlohe.

Or

According to a research at Cambridge University, it doesn’t matter in what order letters in a word are written;. the only important factor is the the first and last letters be in the right place. The rest can be a total mess and you can still read it without a problem. This is because the human mind does not read every letter by itself but the word as a whole.

10 For more than a century, the English aristocracy couldn’t speak English. William the Conqueror tried to learn English at the age of 43 but gave up. He didn’t seem especially fond of the land he had conquered in 1066, spending half of his reign in France and not visiting England at all for five years when in power. Naturally, French-speaking barons were appointed to rule the land.

Within 20 years of the Normans taking power in England, almost all of the local religious institutions were French-speaking. The aristocrats brought with them large retinues and were followed by French tradesmen, who almost certainly mixed bilingually with the English tradesmen. In turn, ambitious Englishmen would have learned French to get ahead in life and mix with the new rulers. Around 10,000 French words entered English in the century after the Norman invasion. There is little to suggest that aristocrats themselves spoke English. It isn’t until the end of the 12th Century that we have evidence of the children of the English aristocracy with English as a first language. In 1204, the English nobility lost their estates in France and adopted English partly as a matter of national pride.

11 One man is credited as being largely responsible for the differences between American and British spelling. Noah Webster, born in West Hartford, Connecticut in 1758, believed that a great emerging nation such as the USA needed a language of its own: American English. Webster found the English in the textbooks of the time to be corrupted by the British aristocracy, with too much French and Classical influence. He was to write American books for American learners, representing a young, proud and forward-thinking nation. Between 1783 and 1785, he produced three books on the English language for American schoolchildren. During his lifetime, 385 editions of his Speller were published.

The modern US spelling of color was initially spelt in the British way, colour, but this changed in later editions. Other differences include the US spelling of center as opposed to the British centre, and traveler instead of traveller. Webster wanted to make spelling more logical, as befitting a nation that was founded on progressive principles. This is a rare example of a dictionary writer trying to lead the English language instead of describe it.

The history of English - Who speaks English?

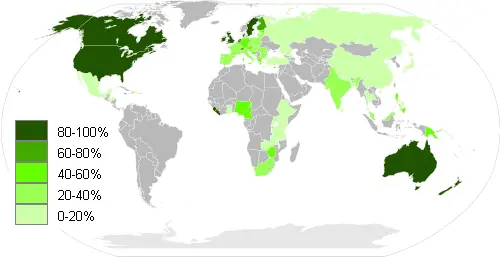

It should be noted here that statistics on the numbers around the world who speak English are unreliable at best. It is notoriously difficult to define quite what is meant by “English speaker”, let alone the definitions of first language, second language, mother tongue, native speaker, etc. What level of competency counts? Does a thick creole (English-based, but completely incomprehensible to a native English speaker) count? Just to add to the confusion, there are at least 40 million people in the nominally English-speaking United States who do NOT speak English. In addition, the figures, of necessity, combine statistics from different sources, different dates, etc. You may well see large variations on any statistics quoted here. But best recent estimates of first languages suggest that Mandarin Chinese has around 800-850 million native speakers, while English and Spanish both have about 330-350 million each. Following on, Hindi speakers number 180-200 million (around 240 million, or possibly much more, when combined with Urdu), Bengali 170-180 million, Arabic 150-220 million, Portuguese 150-180 million, Russian 140-160 million and Japanese roughly 120 million. If second-language speakers are included, Mandarin increases to around 1 billion, English to over 500 million, Spanish to 420-500 million, Hindi/Urdu to around 480 million, and so on, although some estimates for English as a first or second language rise to over a billion. In fact, among English speakers, non-native speakers may now outnumber native speakers by as much as three to one. In terms of total population, in a world approaching 7 billion, the top three countries by population are China (1.3 billion), India (1.2 billion) and USA (about 310 million), followed by Indonesia, Brazil, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nigeria, Russia and Japan. Thus, the USA is by far the most populous English-speaking country and accounts for almost 70% of native English speakers (Britain, by comparison has a population of just over 60 million, and ranks 22nd in the world). India represents the third largest group of English speakers after the USA and UK, even though only 4-5% of its population speaks English (4% of over 1.2 billion is still almost 50 million). However, by some counts as many as 23% of Indians speak English, which would put it firmly in second place, well above Britain. Even Nigeria may have more English speakers than Britain according to some estimates.

Although falling short of official status, English is also an important language in at least twenty other countries, inluding several former British colonies and protectorates, such as Bahrain, Bangladesh, Brunei, Cyprus, Malaysia and the United Arab Emirates. It is the most commonly used unofficial language in Israel and an increasing number of other countries such as Switzerland, the Netherlands, Norway and Germany. Within Europe, an estimated 85% of Swedes can comfortably converse in English, 83% of Danes, 79% of Dutch, 66% in Luxembourg and over 50% in countries such as Finland, Slovenia, Austria, Belgium, and Germany. If the “inner circle” of a language is native first-language speakers and the “outer circle” is second-language speakers and official language countries, there is a third, “expanding circle” of countries which recognize the importance of English as an international language and teach it in schools as their foreign language of choice. English is the most widely taught foreign language in schools across the globe, with over 100 countries - from China to Russia to Israel, Germany, Spain, Egypt, Brazil, etc, etc - teaching it to at least a working level. Over 1 billion people throughout the world are currently learning English, and there are estimated to be more students of English in China alone than there are inhabitants of the USA. A 2006 report by the British Council suggests that the number of people learning English is likely to continue to increase over the next 10-15 years, peaking at around 2 billion, after which a decline is predicted. |

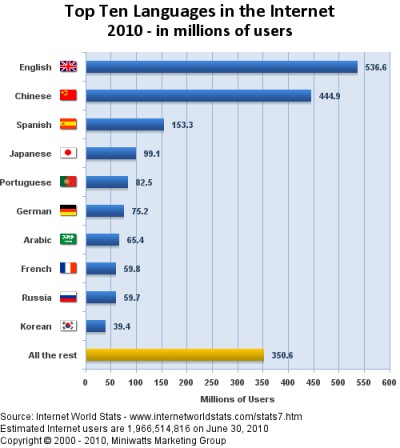

Over 90% of international airlines use English as their language of choice (known as “Airspeak”), and an Italian pilot flying an Italian plane into an Italian airport, for example, contacts ground control in English. The same applies in international maritime communications (“Seaspeak”). Two-thirds of all scientific papers are published in English, and the Science Citation Index reports that as many as 95% of its articles were written in English, even though only half of them came from authors in English-speaking countries. Up to half of all business deals throughout the world are conducted in English. Popular music worldwide is overwhelmingly dominated by English (estimates of up to 95% have been suggested), and American television is available almost everywhere. Half of the world newspapers are in English, and some 75% of the world mail correspondence is in English (the USA alone accounts for 50%). At least 35% of Internet users are English speakers, and estimated 70-80% of the content on the Internet is in English (although reliable figures on this are hard to establish). Many international joint business ventures use English as their working language, even if none of the members are officially English-speaking. For example, it is the working language of the Asian trade group ASEAN and the oil exporting organization OPEC, and it is the official language of the European Central Bank, even though the bank is located in Germany and Britain is not even a member of the Eurozone. Switzerland has three official languages (German, French and Italian and also, in some limited circumstances, Romansh), but it routinely markets itself in English in order to avoid arguments between different areas. Wherever one travels in the word one see sees English signs and advertisements. |

Although a huge number of words have been imported into English from other languages over the history of its development, many English words have been incorporated (particularly in the last century) into foreign languages in a kind of reverse adoption process. Anglicisms such as stop, sport, tennis, golf, weekend, jeans, bar, airport, hotel, etc, are among the most universally used in the world.

But a more amusing exercise is to piece together the English derivations of foreign words where phonetic spelling are used. To give a few random examples, herkot is Ukrainian for “haircut”; muving pikceris is Lithuanian for “movie” or “moving pictures”; ajskrym is Polish for “ice-cream”; schiacchenze is Italian for “shake hands”; etc. Japanese has as many as 20,000 anglicisms in regular use (“Japlish”), including apputodeito (up-to-date), erebata (elevator), raiba intenshibu (labour-intensive), nekutai (neck-tie), biiru (beer), isukrimu (ice-cream), esukareta (escalator), remon (lemon), mai-kaa (my car) and shyanpu setto (shampoo and set), the meanings of which are difficult to fathom until spoken out phonetically. “Russlish” uses phonetic spellings such as seksapil (sex appeal), jeansi (jeans), striptiz (strip-tease), kompyuter (computer), chempion (champion) and shusi (shoes), as well as many exact spellings like rockmusic, discjockey, hooligan, supermarket, etc. German has invented, by analogy, anglicisms that do not even exist in English, such as Pullunder (from pullover), Twens (from teens), Dressman (a word for a male model) and handy (a word for a cellphone). After many centuries of one-way traffic of words from French to English, the flow finally reversed in the middle of the 20th Century, and now anywhere between 1% and 5% of French words are anglicisms, according to some recent estimates. Rosbif (roast beef) has been in the French language for over 350 years, and ouest (west) for 700 years, but popular recent “Franglais” adoptions like le gadget, le weekend, le blue-jeans, le self-service, le cash-flow, le sandwich, le babysitter, le meeting, le basketball, le manager, le parking, le shopping, le snaque-barre, le sweat, le marketing, cool, etc, are now firmly engrained in the language. There is a strong movement within France, under the stern leadership of the venerable Académie Française, to reclaim French from this onslaught of anglicisms, and the country has even passed laws to discourage the use of anglicisms and to protect its own language and culture. New French replacements for English words are being encouraged, such as le logiciel instead of le soft (software), le disc audio-numérique instead of le compact disc (CD), le baladeur instead of le walkman (portable music player), etc. In Québec, the neologism le clavardage (a portmanteau word combining clavier - keyboard - and bavardage - verbal chat) is becoming popular as a replacement for the common anglicism le chat (in the sense of online chat rooms). Norway and Brazil have recently adopted similar measure to keep English out, and this kind of lexical invasion in the form of loanwords is seen by some as the thin end of the wedge, to be strenuously avoided in the interests of national pride and cultural independence. |

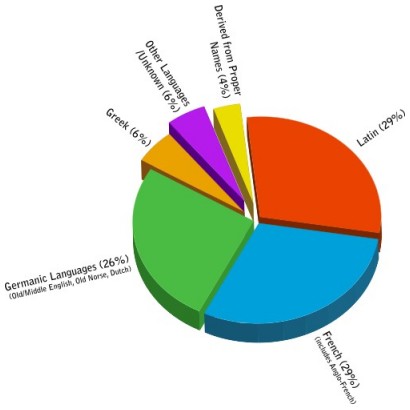

Just how many words there currently are in the English language is open to conjecture. The Global Language Monitor (a Texas-based company that analyzes and tracks worldwide language trends) claims that the English language now boasts over a million words, but in reality it is almost impossible to count the number of words in a language, not least because it is so hard to decide what actually counts as a word. For instance, how are we to treat abbreviations, hypenated words, compound words, compound words with spaces, etc? The latest full revision of the “Oxford English Dictionary”, published in 1989 and considered the premier dictionary of the English language, contains about 615,000 word entries, listed under about 300,000 main entries. This includes some scientific terms, dialect words and slang, but does not include more specialized scientific and technical terms, nor the large number of more recent neologisms coined each passing year. "Webster's Third New International Dictionary”, published in1961, lists 475,000 main headwords. The working vocabulary of the average English speaker, though, is notoriously difficult to assess (it is hard enough to count the words used in written works - estimates of the number of words in the “King James Bible” range from 7,000 to over 10,000, and estimates of Shakespeare’s vocabulary range from 16,000 to over 30,000). An average educated English speaker has perhaps 15,000 to 20,000 words at his or her disposal, although often only around 10% of these are used in an average week’s conversation (typically, we "know" at least 25% more words than we ever actually use). Some studies suggest that just 43 words account for fully half of the words in common use, and just 9 (and, be, have, it, of, the, to, will, you) account for a quarter of the words in any random sample of spoken English. The English lexicon includes words borrowed from an estimated 120 different languages. Attempts have been made to put in context the various influences and sources of modern English vocabulary, although this is necessarily an inexact science. Some studies have put Germanic, French and Latin sources more or less equal at between 26-29% each, with the balance made up of Greek, words derived from proper names, words with no clear etymology and words from other languages. Other studies put the French input higher, the Latin lower and suggest that other languages have contributed as much as 10% of the vocabulary. None of the studies is considered definitive.

The sheer number of English synonyms can make for a rather unwieldy and untidy language at times, though, and its embarrassment of riches can sometime seem a little gratuitous and unnecessary. This is particularly evident in the large number of redundant phrases (composed of two or more synonyms) which are in everyday use, e.g. beck and call, law and order, null and void, safe and sound, first and foremost, trials and tribulations, kith and kin, hale and hearty, peace and quiet, cease and desist, rack and ruin, etc. Also, despite the sheer volume of words in the language, there are still some curious gaps, which have arisen through quirks in its development over the centuries, such as the unused positive forms of common negative words like inept, ineffable, dishevelled, disgruntled, incorrigible, ruthless, disastrous, incessant and unkempt, most of which used to exist but have died out for unknown reasons. Perhaps even stranger, given the generous availability of words, is English’s tendency to load single words with multiple meanings. For example: fine has at least 14 definitions as an adjective, 6 as a noun, 2 as a verb and 2 as an adverb; round has 12 uses as an adjective, 19 as a noun, 12 as a verb, 1 as an adverb and 2 as a preposition; set has an incredible 58 uses as a noun, 126 as a verb and 10 as an adjective (the "Oxford English Dictionary" takes about 60,000 words - the length of a short novel - to describe them all). As in any language, meanings have shifted over time, sometimes many times, but in some cases the same word can has even ended up with two contradictory meanings (contranyms), examples being sanction (which has conflicting meanings of permission to do something, or prevention from doing something), cleave (to cut in half, or to stick together), sanguine (hot-headed and bloodthirsty, or calm and cheerful), ravish (to rape, or to enrapture), fast (stuck firm, or moving quickly), oversight (watchful control, or something not noticed), etc. |

News today

BBC: https://www.bbc.com/news/world

or

CNN: https://edition.cnn.com/

Write a brief summary into your notebook. (10 sentences.) Prepare to share it with the class.

VOA Voice of America (LOW INTERMEDIATE)

Go to VOA website:

https://learningenglish.voanews.com/a/north-south-korean-couples-deal-with-cultural-language-differences/5577355.html

Listen to the story (with headphones in the class) and write all vocabulary in your notebook. Are you able to explain what the story was about?

VOA Voice of America (ADVANCED)

https://projects.voanews.com/making-the-constitution/

Listen to the chapter (with headphones in the class): The history of America. Complete given exercises.

BBC Learning English (INTERMEDIATE)

Go to BBC Learning English:

1. News review:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/learningenglish/english/course/upper-intermediate/unit-1/session-2

2. Pronunciation and double contractions:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/learningenglish/english/course/upper-intermediate/unit-1/session-4

Plus several grammar quizzes:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/learningenglish/english/course/quizzes

Watch the videos (with headphones in the class). Practise pronuciation, vocabulary and grammar. View full vocabulary and grammar references given.