It’s tempting to talk of writing—the art of it, the craft of it, the lifestyle of it—as a kind of romance. Writers of serious literature (according to, at least, many writers of serious literature) do not simply type stark words onto blank pages; instead, they stare into an abyss and reach into their souls and find, if they are fortunate, the swirling fires of Prometheus. “We write to taste life twice, in the moment and in retrospect,” Anaïs Nin said, which is beautiful and true and also objectively incorrect: Writing is delicious work, but it is for the most part simply work. It’s often lonely. It’s rarely romantic. (I am not a writer of serious literature, but I am a writer, and I am writing this while sipping stale coffee from a mug that’s in bad need of a wash.) Writing is a craft in the way that carpentry is a craft: There’s art to it, sure, and a certain inspiration required of it, definitely, but for the most part you’re just sawing and sanding and getting dust in your eyes.

Because of all that, it’s refreshing—and it is also a profound public service— when writers of literature use their public platforms not just to celebrate literature, but also to put the creation of literature in its place. And it’s especially refreshing when writers at the highest levels of the field do that. One of them has been Kazuo Ishiguro, the British novelist and the latest winner of the Nobel Prize.

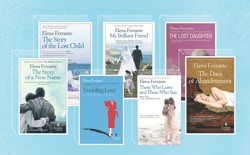

Related StoryElena Ferrante and the Cost of Being an Author

On Thursday, the Nobel Committee announced that Ishiguro is its 2017 laureate for literature—a decision, the Committee noted in its citation, that came in part because the author, “in novels of great emotional force, has uncovered the abyss beneath our illusory sense of connection with the world.” Almost immediately after the announcement was made, a story from The Guardian, written by Ishiguro himself and published in December of 2014, began circulating on social media. The piece is headlined, “Kazuo Ishiguro: How I Wrote The Remains of the Day in Four Weeks.” And it outlines, in great detail, how, indeed, the author overcame writer’s block—made worse by the banal demands of life itself—to summon the words that would become the novel that remains Ishiguro’s most famous contribution to the literary world.

A little bit Draft No. 4 and a little bit The 4-Hour Workweek, Ishiguro’s essay is, just as his fiction, at once spare and revealing. It outlines the period after Ishiguro’s second novel was published—a time that found the 32-year-old flailing professionally and having trouble being productive. So Ishiguro and his wife, Lorna, hatched a plan to jump-start his creativity:

I would, for a four-week period, ruthlessly clear my diary and go on what we somewhat mysteriously called a “Crash.” During the Crash, I would do nothing but write from 9 a.m. to 10:30 p.m., Monday through Saturday. I’d get one hour off for lunch and two for dinner. I’d not see, let alone answer, any mail, and would not go near the phone. No one would come to the house. Lorna, despite her own busy schedule, would for this period do my share of the cooking and housework. In this way, so we hoped, I’d not only complete more work quantitively, but reach a mental state in which my fictional world was more real to me than the actual one.

The goal was method writing, essentially: to create an environment, through force of will, in which the author and his story might be merged into one. It was a plan that demanded intentionally de-romanticizing the act of writing: “Throughout the Crash,” Ishiguro notes, “I wrote free-hand, not caring about the style or if something I wrote in the afternoon contradicted something I’d established in the story that morning. The priority was simply to get the ideas surfacing and growing. Awful sentences, hideous dialogue, scenes that went nowhere—I let them remain and ploughed on.”

It worked. Four weeks later, Ishiguro had a draft of The Remains of the Day. He tinkered with it still, yes. He added and trimmed and honed. For the most part, though, he had, in a concentrated month, completed a masterpiece. He’d spent his year of unproductivity, he notes, doing the background work of the writing—he’d read books by and about British servants, and histories, and “The Danger of Being a Gentleman”—and the Crash came at a time when Ishiguro knew what he needed to know to write what he wanted to write. All that was required was to sit down and do the work. (There’s a German word for that, and that word is Sitzfleisch.)

It’s a helpful reminder to writers of literature both serious and less so—and to anyone who might be intimidated by talk of writing’s metaphysical properties. “If you mix Jane Austen and Franz Kafka then you have Kazuo Ishiguro in a nutshell, but you have to add a little bit of Marcel Proust into the mix,” said Sara Danius, the permanent secretary of The Swedish Academy, explaining the Committee’s choice of Ishiguro. “Then you stir, but not too much, then you have his writings.”

It’s high, and accurate, praise—but it came only after Ishiguro was dedicated enough to sit down, put pen to page, and create those awful sentences, hideous dialogue, and scenes that went nowhere. The author, for four weeks, gave himself the freedom to be terrible—and now he has a Nobel Prize to show for it.

Kommentit

Kirjaudu sisään lisätäksesi tähän kommentin